Taking Care

In awe of Tokyo

Happy Sunday,

Last week I visited Tokyo for the first time. I began to type these stories below as we flew away from Japan, first alongside the Northeast coast of Russia and then onward toward the Arctic Circle.

I was in awe of Tokyo. The further away we flew, the more the feeling grew. This was less the that-was-fun-but-I’m-ready-to-get-home awe and more the I-saw-something-for-the-first-time-and-I-don’t-want-to-unsee-it awe. Maybe my perspective was tipsy from recency bias. Or post-travel glow. Or maybe I was just mildly unhinged from being that close to Russia.

In any case, I returned to the stories this weekend to see how the feeling aged. Awe. I feel it now, as I did then.

These stories are both an attempt to crystallize the magic of Tokyo with the written word and an effort to tunnel closer to the essence of my awe.

To get closer to Truth.

The Waiter

I dined solo the first night. My friends were delayed so I was the first to arrive. I wandered into an emptier restaurant in Asakusa, a pulsing vein of restaurants and shops south of central Tokyo’s Imperial Palace. The restaurant was the love child of a Japanese temple and a cowboy western saloon. I was the only westerner in the place and had to rely on AI-assisted language translations to stumble through every detail on the menu.

When dinner arrived--thin and curly slices of Wagyu beef carpaccio and slippery cold udon noodles--the waiter took notice of how I incorrectly used chopsticks. I was getting by as-is. I wasn’t dropping every bite of food or hopelessly relying on a fork that I didn’t even have. But he took notice of my flawed technique nonetheless, sat down on the barstool to my left and spent the next ten minutes trying to help me improve. He took a pair of chopsticks himself. Lead by example? No cigar. He tried his best English. Something about how to use the index finger? No cigar. He even guided my hand with his. Show me the way? No cigar.

I left that night no better at using chopsticks. Good-enough remained good-enough, that night and for the rest of the trip. But the benevolent and unrelenting effort of this always-smiling man made him feel like an immediate and long-lost friend. He dissolved the distance between us--an age gap, language gap, culture gap, and a skill gap--all evaporating in his warm generosity. He was radiant in his attempt to help. I was hardly three hours into my time in Tokyo, on my first-ever trip to Asia, and yet I left the restaurant that evening awash in a sense of comfort and camaraderie. In the effort of others it is easy to find home.

The Bellhop

A bellhop at the Grand Otani Hotel in central Tokyo took my bags to my room for me against my better judgment. We walked together after I checked in, through a velvety lobby decorated with gold and glass and indistinct carpet patterns and architectural nostalgia for a bygone era. Like the waiter, the bellhop too spoke almost no English. I’m typically a hard No on letting someone else carry my luggage if I am able-bodied. Is it not dramatically self-indulgent? Please sir, I insist, he said, his smile beaming and unflinching across his honest face. Fatigue from a twelve-hour flight over the Pacific turned my staunch ideals to soft Jell-O. I acquiesced. Sure, take my bags. Funny how easily we can drift away from the person we think we are.

His smile beamed brighter as he took the suitcase handle in one hand and the clasped duffel hand straps in the other. When we got to my room I reached for my wallet, racking my brain to remember if I had cash or not. Please have cash, you cheap schmuck. His generosity was prepared to judge my shortsightedness if my wallet were empty, I feared. But it didn’t matter.

As I reached for my wallet, the bellhop immediately retreated. He recoiled backward, almost instinctively, as if I were a hot flame, a venomous snake or a highly-infectious Covid variant. He raised his palms and blocked his body. No sir, that is not necessary. His smile remained genuine, unchanged and serene. His face revealed no hint of the sly hospitality I’m-saying-no-but-I’ll-say-yes-once-you-ask-again set up. Of course I asked again. Are you sure? Please, I insist. Now I was the insistent one. He stood his ground. His full smile continued to beam. He clasped his open palms together and bowed gently toward me. Of course sir, I insist. It is my pleasure to help you. Thank you very much for offering though, I wish you a very pleasant stay in Japan.

Taxi Drivers

We took Taxis and Ubers all around Tokyo. Not all the time, but we were a group of six and many of our days were filled with a cold and biting rain that often devolved into snowy slush. At first I was reluctant to lean on taxis. We’re in Tokyo. let’s experience the city as the locals do. By the end, I was mesmerized by the experience of riding in them-- all of them.

The benefits of convenience aside, the attention to detail of the drivers was remarkable, both in the cleanliness of their cars and the customer experience they created inside of them. It was a cut above any rideshare experience I’d ever set foot in. Drivers fused excellence into every facet of the experience. Uber XLs were luxury sprinter vans with automatic doors. Large taxis were posh, London-like relics with smooth curves, polished shine and grand wheel wells. Small taxis were classics out of a James Bond film, the kind of ride fit for a spy in a tuxedo or newly-weds whisked away from a church. Taxi exteriors glistened in the late Winter sun. Interiors offered plush upholstery. Drivers always wore jackets, if not full suits. They drove with silk white gloves that extended up to the elbow. They got out each time to handle and organize our luggage in the trunk. They walked us toward, and welcomed us in, the automatically-opening passenger doors, bowing and smiling and extending an inviting hand. Welcome, they said, with their entire being. Were we in a ballroom atop the Titanic or in a $14 ride to dinner? Drivers made us feel as if we were royalty, or at least the Kardashians. And they seemed to genuinely enjoy doing so. As if their life’s work looked no further than creating an idyllic customer experience for each rider they served.

Even moments of mild friction with a few drivers further signaled their passion for the minutia of their craft. One of us accidentally defied the rules of a taxi pickup line at a hotel and we were swiftly scolded by the impacted driver. We did not follow the rules and he let us hear it. In another ride, in an earnest attempt to show the driver where we wanted to go, I pulled up Google Maps and, riding shotgun, leaned over to show him while he drove. His gaze laser-focused in front of him, he sternly shooed me away, pointing to the road ahead and belting out something animated in Japanese. I have no idea what he said, but it was apparent it was an outright rejection of the idea that he would take his eyes off the road to look at my phone. How dare I try to distract him from his job.

But these mildly tense moments only amplified my admiration for the attention-to-detail the drivers applied to their craft. They took their work seriously, even if it were only driving a car from point A to point B and not earning any gratuity while doing so. They owned their details. The ride was their fiefdom. The rider experience was theirs to create. Their pride in the details was a world away from our Western frame of reference. No drivers taking their own phone calls. No small talk, woe-is-me storylines or armchair quarterback pontification. No dashboard bobbleheads, bible-thumping bumper stickers or cultural propaganda. No dilapidated interior or torn seats. No body odor. These drivers were not just drivers. They were professionals, inflated with a noble sense of duty. They were artists. They were craftsmen.

The Real McCoy’s

We descended into a below-ground vintage shop--The Real McCoy’s--in the bohemian Shibuya district, a part of the city akin to a cleaner and more orderly version of New York’s Lower East Side. McCoy’s makes American World War II-inspired fashion pieces. That a Japanese store sells American wartime nostalgia was an irony not lost on us. Stacks on stacks of army-green button down shirts. Wooden cubbies full of camo joggers. Piles of neatly-folded cotton crewneck sweatshirts embroidered with Americana badges and symbols. Bomber jackets too cool for me. Midnight-black military boots so clean they certainly never set foot on any actual battlefield. Military trinkets and war paraphernalia filled the negative space--fighter plane figurines, officer trunks, battalion helmets & dog tags. McCoy’s was a stylish adventure back in time. And we were passengers giddy to find ourselves suddenly living in the past.

We buzzed around the store alongside an associate, a young and slender Japanese man, probably in his mid-twenties with a slicked back ponytail and a thin and dark handlebar mustache that extended well past the corners of his mouth. Whenever Jeff or I showed even a hint of interest in a piece, he’d look us up and down to size us up, pick the corresponding size from the rack, unbutton it, and gesture for us to turn around so we could put our arms through the holes and try it on. He was always a step ahead, always in control. His service was exceptional. A personal shopper without a personal shopper.

When he followed Jeff to a different table, I reached for a size bigger in the item I was currently trying on. A perpetual guardian of detail, he of course turned and saw me do this. He then beelined back to me and compulsively re-organized the stack of shirts I had inevitably off-centered when thumbing through the pile in search of an XL. When I turned back to face him, expecting him to confirm this size did indeed fit me quite well, he ignored the fit and looked me straight in my eyes. Without blinking, looking away, or smiling, he said: Please let me get you the size you need. I will help you try it on. Please don’t do it yourself.

His eye contact and his directness were momentarily jarring. Well this is a first. I acknowledged, thanked him, and made sure to seek his help on every remaining piece I tried on that afternoon. When the thrill of shopping expired, as it always does, the store associate gradually glided away from Jeff and I and returned to circling the store, meticulously organizing and reorganizing anything even slightly out of place. Piles straightened. Right angles reconstructed. Color chronology returned. Symmetry rebalanced. Order restored. As I watched him, my sense of surprise from his commitment to rules and order gave way to inspiration, to fizzy awe. Sure he might be a little intense or OCD. But it was a signal of how much he cared--care for what he was doing, care for how he was doing it, and care for who he was serving. Care for the job itself, expressed via a meticulous attention to the little details of his craft. In a menial service-industry job that is overlooked in our achievement-obsessed West? Rare. The wiring in my brain overheated and short-circuited. Can Not Compute.

Clean Streets

The daily volume of human movement through Tokyo is astounding. The greater Tokyo area is home to 38 million people, about twice the population of the greater New York City area. Of these 38 million, 14 million live in Tokyo proper, also about twice the population of Manhattan itself. Tokyo’s subway system handles 40 million daily passenger trips. The world’s busiest train station--the Shinjuku station in Western Tokyo--handles 3.6 million daily passengers alone. In Shibuya, a single crosswalk--the famous Shibuya Crossing-- ferries 3,000 people across the street in a single light change, totaling over 500,000 in a day. Streets are home to well-heeled stampedes. Electronics stores are abuzz with a current of human consumption. Subway stations are beehives. The heart of human activity beats loudly in Tokyo.

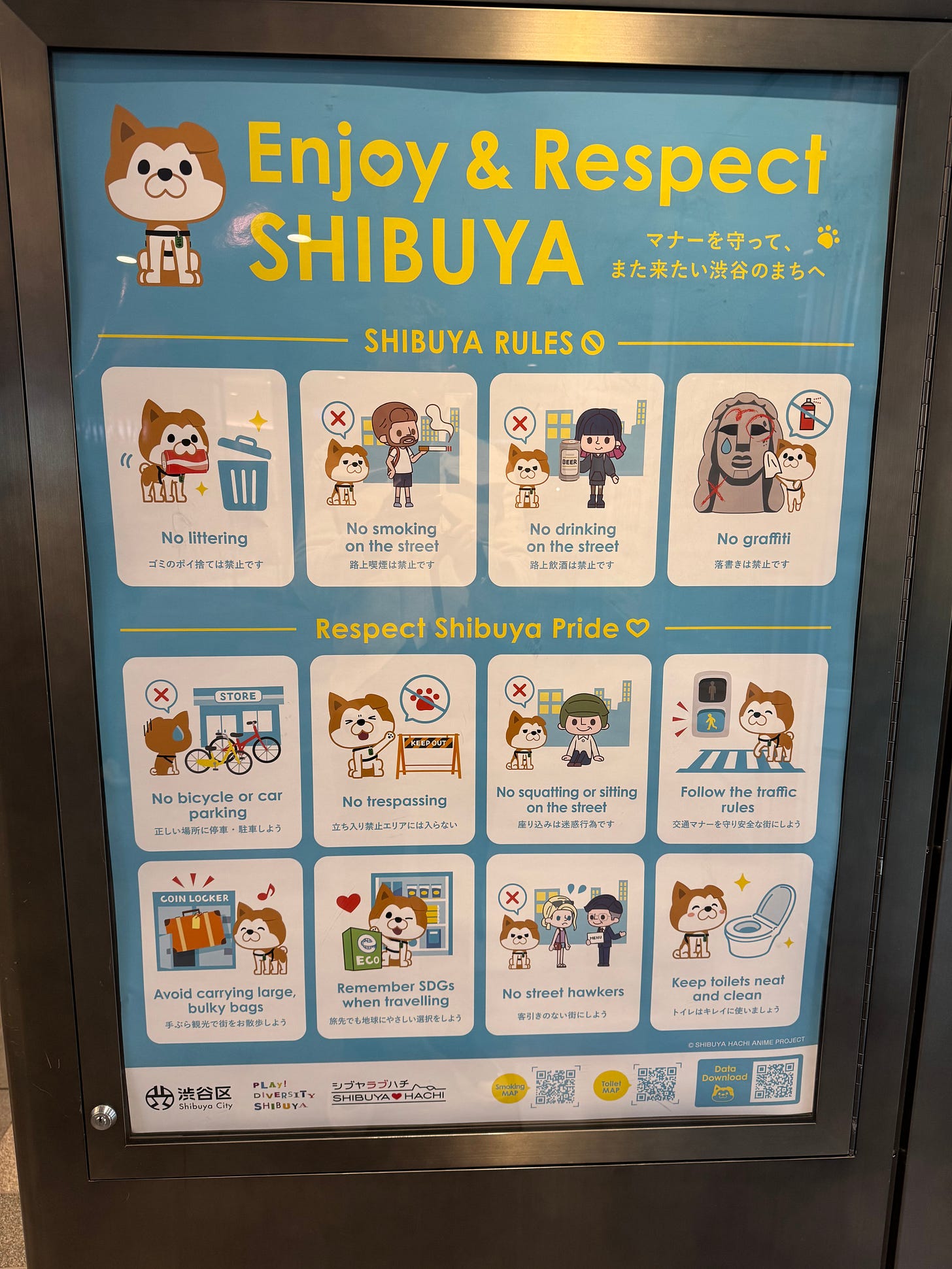

And yet, incredulously, the streets are spotless. No trash. Not even trash cans. No graffiti. No panhandling. No grifting. No homeless. No traffic. The mind struggles to register what the eye sees. How can an abundance of human activity leave behind such little waste?

And the subway? No vandalism. No sign of decay. No stench of dried urine. No begging. No attention-seeking riders playing loud music from their phones. No cars without air conditioning. How can it be that the most notable physical sensation when riding a crowded urban subway is how plump the seat cushions feel?

In the beginning, I found myself chafed by the lack of garbage cans on the street. What am I to do with this empty McDonald’s chicken nuggets carton? How do I rid myself of garbage? By the end of the trip, I had my own answer: put it in your pocket, or your backpack, and dispose of it later. Figure it out. Because everybody else in Tokyo clearly has. Sublime cleanliness? Pleasant. A collective social responsibility? Inspiring.

On our final night, a wet snow fell on the busiest main avenue in Shibuya as I walked home from a standing-only sushi bar. The city was pulsing. Digital billboards promoted beauty products with live video ads of symmetrical faces, high cheekbones and smooth skin. Flashing lights danced atop bar doorways. Music erupted from arcade entrances. Neon signs filled every shop window. Times Square of the East. People of all kinds were out and about. Herds of teenagers in choir uniforms laughed together and took selfies on the sidewalks. Tourists of all shapes and sizes flowed in and out of restaurants, packing them to the brim. Friends and couples walked together, arm-in-arm and hand-in-hand, effortlessly in rhythm. Wet slush may have dampened the streets, but it could not dampen the mood. The engine of Saturday night was leaving the station, rain or shine. There was enough human activity, enough human energy, to imagine the volume of filth and waste left in its wake. The streets of New York City look very different on Sunday morning than they do on Saturday night.

Come Sunday morning, the street was, again to my disbelief, spotless. The slush was gone and the sun was out as I walked the same Shibuya street at 8AM en route to explore one final neighborhood before heading to the airport. No piles of trash bags in front of bars or late night restaurants. No garbage cans full of pizza boxes, styrofoam fast-food containers, cardboard beer cases and energy drink cans. No cigarette butts dotting the curbs. No lingering stench of stale alcohol. No sidewalk vomit. Symptoms of modern excess were astonishingly absent. Did Saturday night even happen? Was this even the same street as eight hours ago? It was as if Shibuya were instead full of tea-totaling churchgoers who had all gone to bed at 9pm. My first thought was to describe the streets as totally rinsed of the Saturday night food and party scene that ended hours earlier. But the word rinsed misses the essence of Tokyo’s awe-inducing cleanliness: there is nothing to rinse away if there is no filth to begin with.

What is this texture in Tokyo that buoys us with awe? Jeff and I wrestled with this question in passing moments toward the end of the trip. It’s pride in one’s craft, Jeff offered, whatever the craft may be. It’s approaching one’s work--driving cars, serving meals, carrying bags, fitting clothes—with an ornate attention to detail. This attention to detail in every product or experience—the neat arrangement of pens in a stationery store, a handmade storefront sign, the spotless floors of Taco Bell, the sound of sharpening knives, the textured paper of the dinner menu—ignites each moment with intention and care.

And, strung together like pearls on a string, these moments of meaning and care make Tokyo shine. In a global world optimizing for scale, Tokyo remains artisanal. In a global world moving ever-faster, Tokyo remains intentional. In a global world fixated on achieving the next thing, Tokyo remains present. Perhaps the most tickling quality of Tokyo is this apparent paradox: that an organism so big can stay so focused on the small.

Neither Tokyo, nor Japan appear perfect. Coronating either as a utopia is to wander off into an unmoored mental la-la land, just as criticizing modern life in the United States is often too negative. No place is without flaws, and Japan appears no exception: birth rates are low, stagflation has hindered its 21st century growth, it is highly exposed to the risk of natural disasters, and it struggles with undercurrents of nationalism and racism rooted in its violent and imperial past. And, like all of us in the modern world, everyone in Tokyo was on their phone 24/7.

But the unwavering care the Japanese put into their craft--no matter how glamorous or mundane the work--mesmerizes and inspires nonetheless. It invites a busy Western mind to engage not with life’s big questions--what career to pursue, where to live, whom to love--but with its subtle ones: How might I create well-being for those around me? Am I fusing pride and attention to detail in the mundanities of my work, or simply going through the motions? Do I work for intrinsic enjoyment or external validation? Am I present in the details of my life or am I perpetually chasing the next big thing?

Tokyo reminds us that grandeur at scale is really just grandeur in the small moments. And its people teach us that treating these moments with care, with intention, and with pride, may be the grandest craft of all.

Love it! Great read - and I couldn't agree more about being awestruck by how different, special, and in a certain way - mature - Toyko feels. (Just went for the first time last July) Clean streets, organized/polite experiences on public transit (!?!!), and generally people just doing things that feel like they're considerate of the good for all vs only what benefits them. Regretfully, I never made it to a Japanese Taco Bell... I guess that gives me a good reason to return... that and selvage denim.